News

-

![Video: CripWisdoms: a coloring book for blind and sighted people]() CripWisdoms: a coloring book for blind and sighted peopleA delightful new book shares disability wisdom while introducing readers to disabled leaders like Dr. Sami Schalk, Alice Wong, Miso Kwak, and Emily Nott. You can order a copy in print or in Braille. Buy the book! Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma, a woman with long black hair, dancing hazel eyes, and medium dark skin, sits...

CripWisdoms: a coloring book for blind and sighted peopleA delightful new book shares disability wisdom while introducing readers to disabled leaders like Dr. Sami Schalk, Alice Wong, Miso Kwak, and Emily Nott. You can order a copy in print or in Braille. Buy the book! Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma, a woman with long black hair, dancing hazel eyes, and medium dark skin, sits... -

![Video: Crispy, Buttery, Berbere Magic at Yosi's Cafe]() Crispy, Buttery, Berbere Magic at Yosi's CafeKitcha fitfit, a dish from Eritrea and Ethiopia, is one of my favorite breakfasts. Chef Azeb uses the freshest ingredients to create tender bites seasoned with delightful berbere—a spice blend starring red chili peppers. If you love kitcha fitfit or are curious to try it, visit Yosi’s Cafe in Oakland, CA. Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma...

Crispy, Buttery, Berbere Magic at Yosi's CafeKitcha fitfit, a dish from Eritrea and Ethiopia, is one of my favorite breakfasts. Chef Azeb uses the freshest ingredients to create tender bites seasoned with delightful berbere—a spice blend starring red chili peppers. If you love kitcha fitfit or are curious to try it, visit Yosi’s Cafe in Oakland, CA. Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma... -

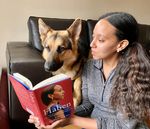

My Book is on Sale!Mylo gave it five stars! If you haven’t read it yet, the ebook and audiobook are on a limited-time promotional price on Apple Books , Kobo , and Libro.fm through January 20.

My Book is on Sale!Mylo gave it five stars! If you haven’t read it yet, the ebook and audiobook are on a limited-time promotional price on Apple Books , Kobo , and Libro.fm through January 20. -

![Video: Haben stands at a tall round table. She's wearing a light-blue dress. Her left hand rests on her Braillenote as she gestures with her right hand. Her expression is earnest as she speaks. Behind her is a bright blue backdrop.]() They wouldn’t hire me—Now I teach employers about ableism. SHRM Linkage Institute Keynote Excerpt.Repeated rejections by hiring managers once fed the corrosive lie that disabled people lack value. My younger self carried that fear. But as my understanding of ableism grew, I began transforming those painful job searches into anecdotes that deliver insights, build connection, and even spark laughter. This clip is from my keynote at the 2025...

They wouldn’t hire me—Now I teach employers about ableism. SHRM Linkage Institute Keynote Excerpt.Repeated rejections by hiring managers once fed the corrosive lie that disabled people lack value. My younger self carried that fear. But as my understanding of ableism grew, I began transforming those painful job searches into anecdotes that deliver insights, build connection, and even spark laughter. This clip is from my keynote at the 2025... -

![Video: Want to Touch the Crown? Deafblind Travel in Edinburgh]() Want to Touch the Crown? Deafblind Travel in EdinburghBlind people can’t see the royal crown, so we should be allowed to touch it, right? Edinburgh Castle wanted to increase accessibility while managing the security concerns posed by large crowds. What do you think of their creative solution? The stunning tactile map featured in this video sits in the public plaza near the Scottish...

Want to Touch the Crown? Deafblind Travel in EdinburghBlind people can’t see the royal crown, so we should be allowed to touch it, right? Edinburgh Castle wanted to increase accessibility while managing the security concerns posed by large crowds. What do you think of their creative solution? The stunning tactile map featured in this video sits in the public plaza near the Scottish... -

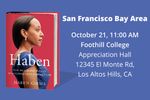

Haben Will be Speaking at Foothill CollegeI'm excited to deliver a keynote for Foothill College's Disability Awareness Month celebrations! Join us on Tuesday October 21 in Los Altos Hills, located near San Jose. The event is open to all, free, and captioning + ASL interpretation will be provided.

Haben Will be Speaking at Foothill CollegeI'm excited to deliver a keynote for Foothill College's Disability Awareness Month celebrations! Join us on Tuesday October 21 in Los Altos Hills, located near San Jose. The event is open to all, free, and captioning + ASL interpretation will be provided. -

Increasing Accessibility in Tanzania One Bank at a TimeBlind people can't handle money, explained the bank manager refusing to let young Rajab Mpilipili open an account. Rajab advocated for himself but the manager would not budge. So the bank lost money, and the determined young student hung on to his. Savor the irony of a bank turning down money. Because of ableism, companies...

Increasing Accessibility in Tanzania One Bank at a TimeBlind people can't handle money, explained the bank manager refusing to let young Rajab Mpilipili open an account. Rajab advocated for himself but the manager would not budge. So the bank lost money, and the determined young student hung on to his. Savor the irony of a bank turning down money. Because of ableism, companies... -

A French Hotel Celebrates Louis BrailleA new hotel in France celebrates innovators, including Louis Braille! His bust appears in the lobby among other great innovators. The Ki Space Hotel & Spa , located near Mr. Braille's hometown of Coupvray just outside Paris, also generously served as a sponsor for the Braille Bicentennial. How thrilling and uplifting to find a French...

A French Hotel Celebrates Louis BrailleA new hotel in France celebrates innovators, including Louis Braille! His bust appears in the lobby among other great innovators. The Ki Space Hotel & Spa , located near Mr. Braille's hometown of Coupvray just outside Paris, also generously served as a sponsor for the Braille Bicentennial. How thrilling and uplifting to find a French... -

![Video: Taste a rare French wine crafted by the blind community]() Taste a rare French wine crafted by the blind communityRaise a glass to Braille! The only blindness organization with its own winery in France, Voir Ensemble crafted this red Bordeaux for the Braille Bicentennial. Descriptive Transcript Beneath the canopy of an outdoor tent, Haben Girma gestures to the table beside her as she speaks with an American accent. Haben: For those of you who...

Taste a rare French wine crafted by the blind communityRaise a glass to Braille! The only blindness organization with its own winery in France, Voir Ensemble crafted this red Bordeaux for the Braille Bicentennial. Descriptive Transcript Beneath the canopy of an outdoor tent, Haben Girma gestures to the table beside her as she speaks with an American accent. Haben: For those of you who... -

![Video: Braille in France: So Many Meanings!]() Braille in France: So Many Meanings!In France, Braille may refer to the tactile reading system, the surname of its inventor, or the call of a strange and gorgeous bird! Thank you to artist and teacher Gabrielle Sauvillers and the Collège André Malraux in Amboise for expanding my understanding of Braille during my visit to France for the Braille Bicentennial. #BrailleFestival...

Braille in France: So Many Meanings!In France, Braille may refer to the tactile reading system, the surname of its inventor, or the call of a strange and gorgeous bird! Thank you to artist and teacher Gabrielle Sauvillers and the Collège André Malraux in Amboise for expanding my understanding of Braille during my visit to France for the Braille Bicentennial. #BrailleFestival... -

![Video: Blind Heroes & Breton Butter: Finding Braille in Saint-Malo]() Blind Heroes & Breton Butter: Finding Braille in Saint-MaloReading Braille out loud over the radio, a young blind woman assists the Allies in the Netflix series "All the Light We Cannot See." The show inspired me to visit Saint-Malo on my journey through France for the Braille Bicentennial. The tourist office offers large print and Braille brochures, videos with French Sign Language, wheelchairs...

Blind Heroes & Breton Butter: Finding Braille in Saint-MaloReading Braille out loud over the radio, a young blind woman assists the Allies in the Netflix series "All the Light We Cannot See." The show inspired me to visit Saint-Malo on my journey through France for the Braille Bicentennial. The tourist office offers large print and Braille brochures, videos with French Sign Language, wheelchairs... -

Visting Voir Ensemble in ParisA community of blind and sighted members, Voir Ensemble is an organization working to increase opportunities for blind people throughout France and francophone Africa. I had the honor of meeting with them in their Paris office, discussing disability rights in the U.S. and France. A core tenet here is l'autonomie, which roughly translates to self-determination....

Visting Voir Ensemble in ParisA community of blind and sighted members, Voir Ensemble is an organization working to increase opportunities for blind people throughout France and francophone Africa. I had the honor of meeting with them in their Paris office, discussing disability rights in the U.S. and France. A core tenet here is l'autonomie, which roughly translates to self-determination.... -

![Video: What is Dinner Table Syndrome?]() What is Dinner Table Syndrome?Having a seat at the table doesn't always mean being included. Deaf and Deafblind people often face dinner table syndrome --- missing out because communication barriers build walls. Watch Haben Girma and Rachel Kolb break it down and share solutions. How do YOU stay connected? Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma, a woman in her thirties with...

What is Dinner Table Syndrome?Having a seat at the table doesn't always mean being included. Deaf and Deafblind people often face dinner table syndrome --- missing out because communication barriers build walls. Watch Haben Girma and Rachel Kolb break it down and share solutions. How do YOU stay connected? Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma, a woman in her thirties with... -

![Video: Don't Miss the Braille Bicentennial in Coupvray, France!]() Don’t Miss Braille Bicentennial in Coupvray, France!Join us in celebrating 200 years of Braille at the Coupvray castle park on September 20, 2025. Visit Coupvray's website for more information about the Braille Bicentennial. Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma, a woman in her thirties with medium dark skin, long black hair, and dancing hazel eyes speaks to the camera. She has a mic...

Don’t Miss Braille Bicentennial in Coupvray, France!Join us in celebrating 200 years of Braille at the Coupvray castle park on September 20, 2025. Visit Coupvray's website for more information about the Braille Bicentennial. Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma, a woman in her thirties with medium dark skin, long black hair, and dancing hazel eyes speaks to the camera. She has a mic... -

Haben is Honored to Speak at the Braille Bicentennial in Coupvray, FranceJoin us in celebrating 200 years of Braille! When Louis Braille became blind in 1812, schools lacked an effective way to teach reading and writing to blind students. After extensive experimentation, he developed the tactile reading system named after him. Today, countless blind people all over the world study textbooks, read recipes, and write computer...

Haben is Honored to Speak at the Braille Bicentennial in Coupvray, FranceJoin us in celebrating 200 years of Braille! When Louis Braille became blind in 1812, schools lacked an effective way to teach reading and writing to blind students. After extensive experimentation, he developed the tactile reading system named after him. Today, countless blind people all over the world study textbooks, read recipes, and write computer... -

Making Space is a Resource for Job SeekersDo you know a disabled job seeker? Tell them about Making Space, an organization connecting disabled people with employers vetted for accessibility. Joining and taking their training courses is free for job seekers. Founders Keely Cat-Wells and Sophie Morgan , both disabled women tired of workplace discrimination, joined forces to smash systemic barriers. I finally...

Making Space is a Resource for Job SeekersDo you know a disabled job seeker? Tell them about Making Space, an organization connecting disabled people with employers vetted for accessibility. Joining and taking their training courses is free for job seekers. Founders Keely Cat-Wells and Sophie Morgan , both disabled women tired of workplace discrimination, joined forces to smash systemic barriers. I finally... -

![Video: I broke my ankle and now have 3 disabilities! My top 3 perks of using a wheelchair.]() I broke my ankle and now have 3 disabilities! My top 3 perks of using a wheelchair.I broke my ankle, and let me tell you: using a wheelchair while Deafblind is an experience for the next book! In honor of #DisabilityPrideMonth here are my favorite things about using a chair. Thank you to my friend Dr. H'Sien Hayward , a psychologist and experienced wheelchair user, for patiently answering all my chair...

I broke my ankle and now have 3 disabilities! My top 3 perks of using a wheelchair.I broke my ankle, and let me tell you: using a wheelchair while Deafblind is an experience for the next book! In honor of #DisabilityPrideMonth here are my favorite things about using a chair. Thank you to my friend Dr. H'Sien Hayward , a psychologist and experienced wheelchair user, for patiently answering all my chair... -

![Video: My first Braille Map Experience at a Garden: Seattle Sensory Garden]() My first Braille Map Experience at a Garden: Seattle Sensory GardenThe first time I experienced a Braille map of a garden was in Seattle. Thoughtfully designed exhibits throughout this oasis encourage us to savor all our senses; they even have a tribute to proprioception, the sense for knowing where your body is in space, a kind of internal GPS. While most gardens focus on sight,...

My first Braille Map Experience at a Garden: Seattle Sensory GardenThe first time I experienced a Braille map of a garden was in Seattle. Thoughtfully designed exhibits throughout this oasis encourage us to savor all our senses; they even have a tribute to proprioception, the sense for knowing where your body is in space, a kind of internal GPS. While most gardens focus on sight,... -

![Video: Touch Tour at the Museum of Flight in Seattle]() Touch Tour at the Museum of Flight in SeattleImagine a future where blind people building planes, flying planes, and shaping aviation policy is so common it ceases to be remarkable. Seattle's Museum of Flight has a selection of planes both blind and sighted people are encouraged to touch. Blind guests can also arrange an extended touch tour, and during my visit a pilot...

Touch Tour at the Museum of Flight in SeattleImagine a future where blind people building planes, flying planes, and shaping aviation policy is so common it ceases to be remarkable. Seattle's Museum of Flight has a selection of planes both blind and sighted people are encouraged to touch. Blind guests can also arrange an extended touch tour, and during my visit a pilot... -

![Video: One Deafblind, Unpaid Protestor]() Disabled People are Also ProtestingFor many disabled people, showing up at a protest requires planning. Will there be an ASL interpreter or will you need to find a volunteer? Will the space be wheelchair accessible? For me, as a Deafblind person, I need a seat or table for my Braille computer and keyboard. Organizers who share detailed accessibility information...

Disabled People are Also ProtestingFor many disabled people, showing up at a protest requires planning. Will there be an ASL interpreter or will you need to find a volunteer? Will the space be wheelchair accessible? For me, as a Deafblind person, I need a seat or table for my Braille computer and keyboard. Organizers who share detailed accessibility information... -

![Video: Love in the Lead: International Guide Dog Day]() Love in the Lead: International Guide Dog DayIt's International Guide Dog Day! Please share this video and encourage people to support The Seeing Eye . You can volunteer to help raise Seeing Eye puppies or make a donation by going to SeeingEye.org . Descriptive Transcript A German Shepherd dog on a big fluffy bed gazes toward the camera with his ears pointed....

Love in the Lead: International Guide Dog DayIt's International Guide Dog Day! Please share this video and encourage people to support The Seeing Eye . You can volunteer to help raise Seeing Eye puppies or make a donation by going to SeeingEye.org . Descriptive Transcript A German Shepherd dog on a big fluffy bed gazes toward the camera with his ears pointed.... -

![Video: Seeing Eye Dog Mylo Navigates Amsterdam]() Seeing Eye Dog Mylo Navigates AmsterdamAs cities embrace bicycles, let's not forget pedestrians. Thousands of bikes parked on sidewalks in Amsterdam force pedestrians into streets where they face even more bikes. Seeing Eye dog Mylo rose to the challenge, and I felt safer having him by my side. It's my hope city planners around the world design obstruction-free pedestrian pathways,...

Seeing Eye Dog Mylo Navigates AmsterdamAs cities embrace bicycles, let's not forget pedestrians. Thousands of bikes parked on sidewalks in Amsterdam force pedestrians into streets where they face even more bikes. Seeing Eye dog Mylo rose to the challenge, and I felt safer having him by my side. It's my hope city planners around the world design obstruction-free pedestrian pathways,... -

Haben Will be Speaking at the University of HartfordI am excited to deliver a keynote at the University of Hartford on April 9th! The university has generously opened up this event to all, and captioning & ASL interpretation will be provided. Free registration: Spring 2025 Rogow Distinguished Visiting Lecturer -- University of Hartford

Haben Will be Speaking at the University of HartfordI am excited to deliver a keynote at the University of Hartford on April 9th! The university has generously opened up this event to all, and captioning & ASL interpretation will be provided. Free registration: Spring 2025 Rogow Distinguished Visiting Lecturer -- University of Hartford -

Dosa Cones Pair Perfectly with Ice CreamDosa Cones Pair Perfectly with Ice Cream Dosa cones with heavenly ice cream keep me coming back to Koolfi Creamery. They have Indian-inspired flavors like mango lassi, as well as classics like cookies and cream. Their delicious dosa cones are vegan and gluten-free. You can find Koolfi Creamery in San Francisco and San Leandro, California....

Dosa Cones Pair Perfectly with Ice CreamDosa Cones Pair Perfectly with Ice Cream Dosa cones with heavenly ice cream keep me coming back to Koolfi Creamery. They have Indian-inspired flavors like mango lassi, as well as classics like cookies and cream. Their delicious dosa cones are vegan and gluten-free. You can find Koolfi Creamery in San Francisco and San Leandro, California.... -

Advocating with Eric DozierEric Dozier is a cultural activist skillfully weaving stories and music to bring people together. He taught me the fascinating history behind Bob Marley's song, "War." Back in 1963 Emperor Haile Selassie spoke before the United Nations calling for the end of apartheid. Bob Marley adapted the speech into a song people still play today....

Advocating with Eric DozierEric Dozier is a cultural activist skillfully weaving stories and music to bring people together. He taught me the fascinating history behind Bob Marley's song, "War." Back in 1963 Emperor Haile Selassie spoke before the United Nations calling for the end of apartheid. Bob Marley adapted the speech into a song people still play today.... -

When Mentors Become FriendsFighting discrimination from coast to coast, Deepa Goraya is a disability rights attorney. We met when she was a law student and I was in college wondering if I, too, could go to law school. Deepa generously answered my questions about law school as a blind student, sparking a wonderful friendship. She now lives in...

When Mentors Become FriendsFighting discrimination from coast to coast, Deepa Goraya is a disability rights attorney. We met when she was a law student and I was in college wondering if I, too, could go to law school. Deepa generously answered my questions about law school as a blind student, sparking a wonderful friendship. She now lives in... -

![Video: Haben, Daniela, and her husband José stand together on a sunny sidewalk. Haben wears a blue dress, Daniela wears a green shirt and jeans, and José wears a Navy blue shirt, khakis, and an Apple Watch. Next to German Shepherd Mylo is Rosie, a black lab, and beside José sits a yellow lab sweetly looking at the camera. Behind the smiling group, across the street, is a warm restaurant with indoor and outdoor seating.]() While Blind People use Tech, the Creativity is OursWhile Blind People use Tech, the Creativity is Ours Some sighted people assume screenreaders and other disability tech does all the work for blind people. Instead of saying "Carla wrote the report", her manager simply says "she used a screenreader", as if credit for the report rests with the screenreader. This kind of messaging impacts...

While Blind People use Tech, the Creativity is OursWhile Blind People use Tech, the Creativity is Ours Some sighted people assume screenreaders and other disability tech does all the work for blind people. Instead of saying "Carla wrote the report", her manager simply says "she used a screenreader", as if credit for the report rests with the screenreader. This kind of messaging impacts... -

![Video: Haben Girma and Mychal Threets: The Mental Health and Disability Connection]() Haben Girma and Mychal Threets: The Mental Health and Disability ConnectionThank you to the Berkeley Public Library for hosting this conversation between Haben Girma and Mychal Threets! This clip is an excerpt from the library's YouTube page. Video description Haben, Mychal, and an ASL interpreter sit in the front of a large room. Haben, a black woman in her 30s, wears a colorful flowing dress....

Haben Girma and Mychal Threets: The Mental Health and Disability ConnectionThank you to the Berkeley Public Library for hosting this conversation between Haben Girma and Mychal Threets! This clip is an excerpt from the library's YouTube page. Video description Haben, Mychal, and an ASL interpreter sit in the front of a large room. Haben, a black woman in her 30s, wears a colorful flowing dress.... -

Eating at Ziryab, a Deaf-owned restaurant in BarcelonaEating at Ziryab, a Deaf-owned restaurant in Barcelona Disabled people bring innovative thinking to organizations, and disabled-owned businesses spark unforgettable experiences. Ziryab hires Deaf and hearing employees, and one of the owners is Deaf. It's an extremely popular restaurant in Barcelona. Why do you think that is? Descriptive Transcript Haben and her Seeing Eye dog...

Eating at Ziryab, a Deaf-owned restaurant in BarcelonaEating at Ziryab, a Deaf-owned restaurant in Barcelona Disabled people bring innovative thinking to organizations, and disabled-owned businesses spark unforgettable experiences. Ziryab hires Deaf and hearing employees, and one of the owners is Deaf. It's an extremely popular restaurant in Barcelona. Why do you think that is? Descriptive Transcript Haben and her Seeing Eye dog... -

![Video: Sensory Gardens: Ireland Versus Sweden]() Sensory Gardens: Ireland vs SwedenDreaming of a garden oasis? Allow me to share my experiences visiting the Garden for the Blind in Dublin, Ireland, and a sensory garden in Lund, Sweden. Each one teaches an accessibility feature communities can add to create beautiful, multisensory gardens. Descriptive Transcript Haben wears a short-sleeved navy blue dress, with her elbow resting on...

Sensory Gardens: Ireland vs SwedenDreaming of a garden oasis? Allow me to share my experiences visiting the Garden for the Blind in Dublin, Ireland, and a sensory garden in Lund, Sweden. Each one teaches an accessibility feature communities can add to create beautiful, multisensory gardens. Descriptive Transcript Haben wears a short-sleeved navy blue dress, with her elbow resting on... -

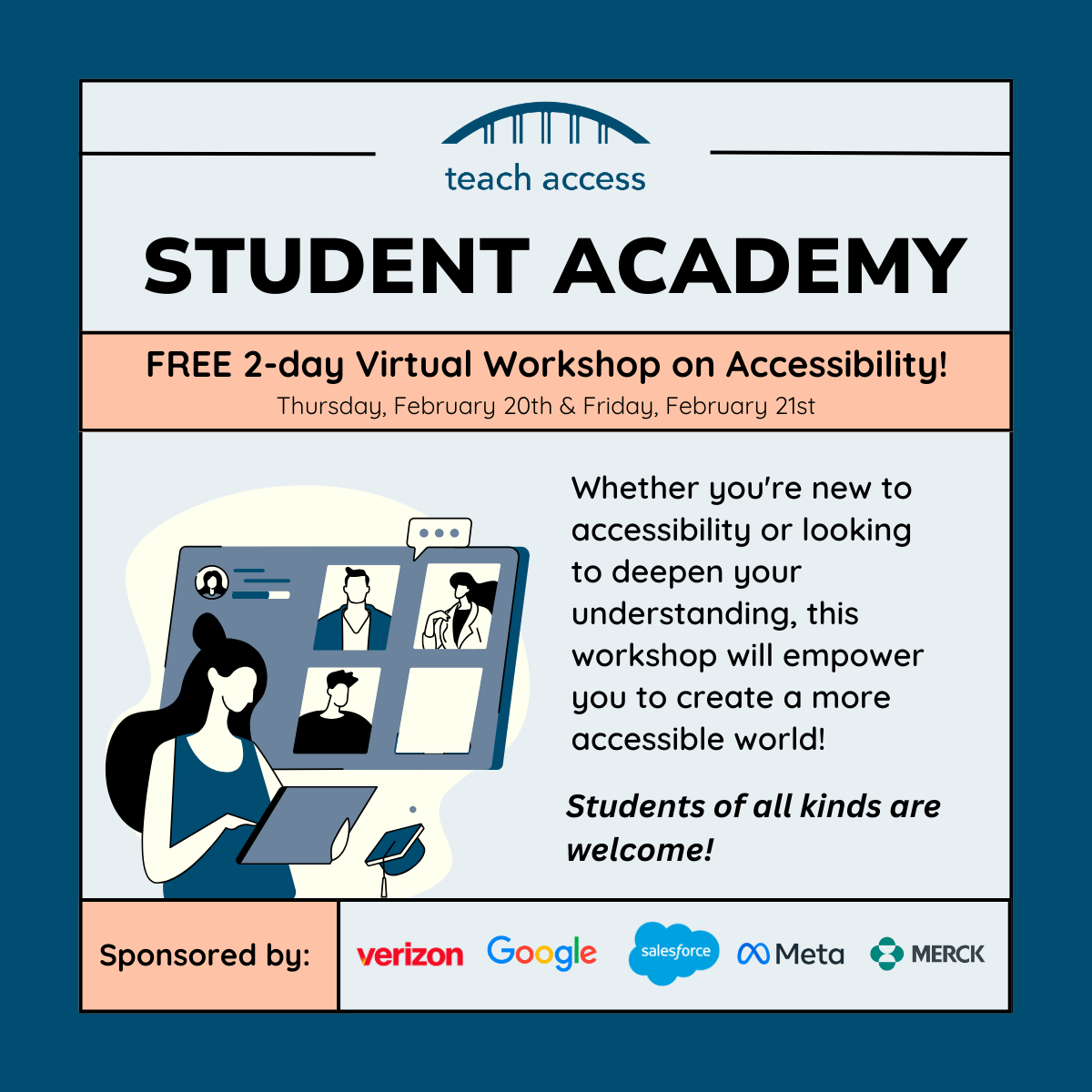

![Video: Teach Access Student Academy. Free 2 day virtual workshop on accessibility! Thursday, February 20th & Friday, February 21st. Whether you're new to accessibility or looking to deepen your understanding, this workshop will empower you to create a more accessible world! Students of all kinds are welcome. Sponsored by verizon, google, salesforce, meta, and Merck.]() Learn Accessibility Skills at the Teach Access Student AcademyLearn Accessibility Skills at the Teach Access Student Academy Increase your accessibility skills through the Teach Access Student Academy, a free virtual workshop on February 20 and 21. Register Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma, a Black woman in her thirties, stands in front of a blue wall. Haben: Do you want to learn more about accessibility?...

Learn Accessibility Skills at the Teach Access Student AcademyLearn Accessibility Skills at the Teach Access Student Academy Increase your accessibility skills through the Teach Access Student Academy, a free virtual workshop on February 20 and 21. Register Descriptive Transcript Haben Girma, a Black woman in her thirties, stands in front of a blue wall. Haben: Do you want to learn more about accessibility?... -

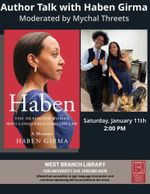

Join Haben Girma & Mychal Threets at the Berkeley Public LibraryAuthor Haben Girma and librarian Mychal Threets invite you to the Berkeley Public Library, West Branch, for a conversation on disability stories, mental health, and accessibility. Join us in person or on Zoom. ASL interpretation, captioning, and the space is wheelchair accessible. Saturday January 11, 2:00 pm Pacific Berkeley Public Library Page with Zoom Link:...

Join Haben Girma & Mychal Threets at the Berkeley Public LibraryAuthor Haben Girma and librarian Mychal Threets invite you to the Berkeley Public Library, West Branch, for a conversation on disability stories, mental health, and accessibility. Join us in person or on Zoom. ASL interpretation, captioning, and the space is wheelchair accessible. Saturday January 11, 2:00 pm Pacific Berkeley Public Library Page with Zoom Link:... -

World Braille Day 2025World Braille Day is January 4th, the birthday of blind inventor and teacher Louis Braille. Help us spread Braille accessibility around the globe! World Braille Day 2025 Watch this video on YouTube](https://youtu.be/VFFOSFMYysA) Two women sit in red chairs on the lower deck of a ferry. Haben Girma, a Black woman in her thirties, types on...

World Braille Day 2025World Braille Day is January 4th, the birthday of blind inventor and teacher Louis Braille. Help us spread Braille accessibility around the globe! World Braille Day 2025 Watch this video on YouTube](https://youtu.be/VFFOSFMYysA) Two women sit in red chairs on the lower deck of a ferry. Haben Girma, a Black woman in her thirties, types on... -

Haben Will Speak at the Berkeley Public LibraryLiteracy ambassador Mychal Threets will chat with Haben Girma, author of Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law. Serving up captivating stories sprinkled with humor, their conversation will cover disability rights, mental health, and how to advocate for a barrier-free world. A Q&A will follow, and copies of Haben's book will be available for...

Haben Will Speak at the Berkeley Public LibraryLiteracy ambassador Mychal Threets will chat with Haben Girma, author of Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law. Serving up captivating stories sprinkled with humor, their conversation will cover disability rights, mental health, and how to advocate for a barrier-free world. A Q&A will follow, and copies of Haben's book will be available for... -

Yes, Disabled People Can Be DoctorsDr. O uses a wheelchair, and he's working toward a future where the idea of disabled people becoming doctors no longer surprises people. I had the honor of sharing the stage with him at the AAMC Annual Meeting, teaching medical schools about the need to increase accessibility for students. Dr. Oluwaferanmi O. Okanlami, MD, MS...

Yes, Disabled People Can Be DoctorsDr. O uses a wheelchair, and he's working toward a future where the idea of disabled people becoming doctors no longer surprises people. I had the honor of sharing the stage with him at the AAMC Annual Meeting, teaching medical schools about the need to increase accessibility for students. Dr. Oluwaferanmi O. Okanlami, MD, MS... -

![Video: Trying Vegan Donuts in Berlin]() Trying Vegan Donuts in BerlinVideo description I'm sitting at a picnic table with three colorful round pastries in front of me. Behind me is my German Shepherd Seeing Eye dog, and a cobblestone square lined with trees. Haben: This is going to be my first vegan donut experience. These are from Brammibal's, and they're actually the first fully vegan...

Trying Vegan Donuts in BerlinVideo description I'm sitting at a picnic table with three colorful round pastries in front of me. Behind me is my German Shepherd Seeing Eye dog, and a cobblestone square lined with trees. Haben: This is going to be my first vegan donut experience. These are from Brammibal's, and they're actually the first fully vegan... -

Haben will be Speaking at Washington University’s Olin Business SchoolI'm thrilled to be speaking at Washington University's Olin Business School on Friday, December 6th. The hybrid event in Saint Louis, Missouri is open to the public, and ASL interpretation will be provided. Register at this link: Registration

Haben will be Speaking at Washington University’s Olin Business SchoolI'm thrilled to be speaking at Washington University's Olin Business School on Friday, December 6th. The hybrid event in Saint Louis, Missouri is open to the public, and ASL interpretation will be provided. Register at this link: Registration -

Centering Disability Justice at the World Health SummitFor the first time, the World Health Summit held a high impact session centering health equity for disabled people. The enthusiasm of leaders from around the world underscored the need to address disability justice in all future health summits. I had the honor of moderating this historic session in Berlin on October 13, 2024. Key...

Centering Disability Justice at the World Health SummitFor the first time, the World Health Summit held a high impact session centering health equity for disabled people. The enthusiasm of leaders from around the world underscored the need to address disability justice in all future health summits. I had the honor of moderating this historic session in Berlin on October 13, 2024. Key... -

![Video: Take a Tactile Tour of the Healthy Materials Lab]() Take a Tactile Tour of the Healthy Materials LabBlind and sighted people can learn about cutting edge textiles at the Healthy Materials Lab. Taking a tactile tour introduced me to textures I'd read about but never felt, and others that completely surprised me. Located on the Parsons School of Design campus, part of The New School in New York City, the lab gives...

Take a Tactile Tour of the Healthy Materials LabBlind and sighted people can learn about cutting edge textiles at the Healthy Materials Lab. Taking a tactile tour introduced me to textures I'd read about but never felt, and others that completely surprised me. Located on the Parsons School of Design campus, part of The New School in New York City, the lab gives... -

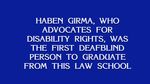

![Video: Designing with Disability Pride: Professor Sugandha Gupta & Haben Girma at Parsons School of Fashion]() Designing with Disability Pride: Professor Sugandha Gupta & Haben Girma at Parsons School of FashionIf you've ever felt isolated and wondered how to build community, if you're frustrated with ableism and dream of designing in ways that no longer marginalize people, then you'll appreciate this video from the Parsons School of Fashion. Parsons' Disabled Fashion Student Program hosted this powerful conversation on October 16, 2024 at The New School...

Designing with Disability Pride: Professor Sugandha Gupta & Haben Girma at Parsons School of FashionIf you've ever felt isolated and wondered how to build community, if you're frustrated with ableism and dream of designing in ways that no longer marginalize people, then you'll appreciate this video from the Parsons School of Fashion. Parsons' Disabled Fashion Student Program hosted this powerful conversation on October 16, 2024 at The New School... -

Apple’s Impressive AirPods Pro 2 Hearing Aids Launch a New Era of Health TechApple gave me early access to their groundbreaking AirPods Pro 2 hearing aids, and the chance to talk to Vice President of Health Dr. Sumbul Desai and Director of Global Accessibility Policy and Initiatives, Sarah Herrlinger. Designed for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss, these over-the-counter hearing aids provide an easy way to explore...

Apple’s Impressive AirPods Pro 2 Hearing Aids Launch a New Era of Health TechApple gave me early access to their groundbreaking AirPods Pro 2 hearing aids, and the chance to talk to Vice President of Health Dr. Sumbul Desai and Director of Global Accessibility Policy and Initiatives, Sarah Herrlinger. Designed for adults with mild to moderate hearing loss, these over-the-counter hearing aids provide an easy way to explore... -

Uber Keeps Denying Service to Blind People with Guide Dogs – Join the Protest!Uber and Lyft frequently deny service to blind people with guide dogs. Help advocate for our civil rights by joining the National Federation of the Blind's Rideshare Rally in San Francisco on October 15, 10 am to 3 pm, outside the Uber and Lyft headquarters. More info . You can also share your experiences with...

Uber Keeps Denying Service to Blind People with Guide Dogs – Join the Protest!Uber and Lyft frequently deny service to blind people with guide dogs. Help advocate for our civil rights by joining the National Federation of the Blind's Rideshare Rally in San Francisco on October 15, 10 am to 3 pm, outside the Uber and Lyft headquarters. More info . You can also share your experiences with... -

Haben’s Interview with Vision AustraliaBlind Australians campaigned for Vision Australia to open recruitment for their CEO position. Considering job applicants both inside and outside the agency would increase the opportunity for Vision Australia to hire their very first CEO who is blind. Hundreds of people signed the petition, and Vision Australia demonstrated true leadership by listening to blind people...

Haben’s Interview with Vision AustraliaBlind Australians campaigned for Vision Australia to open recruitment for their CEO position. Considering job applicants both inside and outside the agency would increase the opportunity for Vision Australia to hire their very first CEO who is blind. Hundreds of people signed the petition, and Vision Australia demonstrated true leadership by listening to blind people... -

I Ate Bugs in Australia!Bug rolls are popular on the Gold Coast. Video description: Haben sits at a beachside restaurant, and on the table in front of her are two small sandwiches. They have a golden brioche bun, lettuce, sauce, and a fried patty. Haben: Australian food is fantastic! And the names for the items are really delightful. This...

I Ate Bugs in Australia!Bug rolls are popular on the Gold Coast. Video description: Haben sits at a beachside restaurant, and on the table in front of her are two small sandwiches. They have a golden brioche bun, lettuce, sauce, and a fried patty. Haben: Australian food is fantastic! And the names for the items are really delightful. This... -

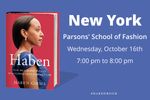

Haben Will Speak at the Parsons’ School of FashionJoin us at the Parsons' School of Fashion for a lively conversation on accessibility, disability justice, and joyful designs. Registration is free, and wheelchair access, captioning, and ASL interpretation will be provided. Excited to share the stage with Sugandha Gupta, an award-winning artist, Assistant Professor of Fashion Design and Social Justice, and a wonderful friend....

Haben Will Speak at the Parsons’ School of FashionJoin us at the Parsons' School of Fashion for a lively conversation on accessibility, disability justice, and joyful designs. Registration is free, and wheelchair access, captioning, and ASL interpretation will be provided. Excited to share the stage with Sugandha Gupta, an award-winning artist, Assistant Professor of Fashion Design and Social Justice, and a wonderful friend.... -

Hire Disabled Leaders, Especially at Disability OrganizationsWhen hiring for executive roles at disability organizations, isn't it better to select the most qualified leader regardless of whether they have a disability? Disability experience should be part of the qualification criteria for these jobs. These jobs involve representing the disabled community and speaking for the disability community. For example, the head of a...

Hire Disabled Leaders, Especially at Disability OrganizationsWhen hiring for executive roles at disability organizations, isn't it better to select the most qualified leader regardless of whether they have a disability? Disability experience should be part of the qualification criteria for these jobs. These jobs involve representing the disabled community and speaking for the disability community. For example, the head of a... -

Trying Vegemite, The Famous Australian SpreadTrying Vegemite for the first time. A blend of vegetable extracts, B vitamins, and beer production leftovers, the spread packs a strong punch! Australians have eaten Vegemite for over a hundred years now. Descriptive Transcript Seated at an outdoor cafe, Haben has a plate with toast covered in a dark brown paste. Haben: When I...

Trying Vegemite, The Famous Australian SpreadTrying Vegemite for the first time. A blend of vegetable extracts, B vitamins, and beer production leftovers, the spread packs a strong punch! Australians have eaten Vegemite for over a hundred years now. Descriptive Transcript Seated at an outdoor cafe, Haben has a plate with toast covered in a dark brown paste. Haben: When I... -

![Video: Nessa and Haben sit on a stone pedestal, and behind them, with one monstrous paw on that same pedestal, is the scariest-looking koala. Black, white, and blue paint across his large body (possibly six feet tall) match the name the artists gave this sculpture: Darth Vader. His eyes glare with the face of an old, hooded person. The sculpture stands in the forest, and birds talk throughout the video. Haben's Seeing Eye dog stands by, a bit bored.]() Learning “Koala” in Australian Sign Language (Auslan)Happy International Week of the Deaf! It's technically next week, but let's celebrate every week! I'm learning Australian Sign Language (Auslan) from Vanessa Vlajkovic. We're both Deafblind and tactile signing. Learning "Koala" in Australian Sign Language (Auslan) Video description: Nessa and Haben sit on a stone pedestal, and behind them, with one monstrous paw on...

Learning “Koala” in Australian Sign Language (Auslan)Happy International Week of the Deaf! It's technically next week, but let's celebrate every week! I'm learning Australian Sign Language (Auslan) from Vanessa Vlajkovic. We're both Deafblind and tactile signing. Learning "Koala" in Australian Sign Language (Auslan) Video description: Nessa and Haben sit on a stone pedestal, and behind them, with one monstrous paw on... -

Haben Speaking at the University of Cincinnati on September 25thIf you're in the Cincinnati area, join us for Digital Inclusion Day on September 25. You can register for my keynote at this link. Registration is free. Captioning & ASL interpretation will be provided. Register

Haben Speaking at the University of Cincinnati on September 25thIf you're in the Cincinnati area, join us for Digital Inclusion Day on September 25. You can register for my keynote at this link. Registration is free. Captioning & ASL interpretation will be provided. Register -

![Video: Haben and Seeing Eye dog Mylo stand next to a young woman. They're all smiling, and behind them is the Sydney Opera House, the bright blue water of the harbor, and the bridge.]() Sydney Opera House Tactile TourHow does a building look like sails, shells, and boats? The Sydney Opera House recently installed a tactile model for blind guests! Sydney Opera House Tactile Tour Descriptive Transcript Haben (Voiceover): The Sydney Opera House has a tactile model. She leans down to touch the bronze coated sculpture sitting on a low pedestal. The shape...

Sydney Opera House Tactile TourHow does a building look like sails, shells, and boats? The Sydney Opera House recently installed a tactile model for blind guests! Sydney Opera House Tactile Tour Descriptive Transcript Haben (Voiceover): The Sydney Opera House has a tactile model. She leans down to touch the bronze coated sculpture sitting on a low pedestal. The shape... -

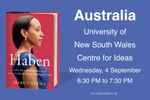

Haben Speaks at the University of New South WalesWill you try vegemite? ABC journalist Nas Campanella posed this question during our keynote at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. We discovered many similarities in the Australian and American disability experiences. Disability camps facilitate connection, allowing disabled people to share adaptive techniques and disability pride. But disability organizations need to do more...

Haben Speaks at the University of New South WalesWill you try vegemite? ABC journalist Nas Campanella posed this question during our keynote at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. We discovered many similarities in the Australian and American disability experiences. Disability camps facilitate connection, allowing disabled people to share adaptive techniques and disability pride. But disability organizations need to do more... -

You have a Voice: Excerpt from the White House Disability Pride Month ConveningThey tried to silence her. They told her to limit her voice to disability issues, but Helen Keller never stopped advocating for human rights. You, too, have a voice. Keep advocating! This video is an excerpt from the White House Disability Pride Month Convening. The entire recording is on the White House YouTube channel. Descriptive...

You have a Voice: Excerpt from the White House Disability Pride Month ConveningThey tried to silence her. They told her to limit her voice to disability issues, but Helen Keller never stopped advocating for human rights. You, too, have a voice. Keep advocating! This video is an excerpt from the White House Disability Pride Month Convening. The entire recording is on the White House YouTube channel. Descriptive... -

Haben Will be Speaking at the University of New South WalesI'm thrilled to be speaking in Sydney with Naz Campanella, an Australian Broadcasting Corporation journalist and the first blind newsreader to run a studio live to air. Join us for a lively conversation on disability advocacy, accessible travel, and the need for more disability stories. This talk is open to everyone and free. Please share...

Haben Will be Speaking at the University of New South WalesI'm thrilled to be speaking in Sydney with Naz Campanella, an Australian Broadcasting Corporation journalist and the first blind newsreader to run a studio live to air. Join us for a lively conversation on disability advocacy, accessible travel, and the need for more disability stories. This talk is open to everyone and free. Please share... -

We All Need Accommodations: Excerpt From The White House Disability Pride Month Convening.The euphemism Special Needs, after many years of service, has filed for retirement. Nondisabled people receive countless supports, so why should supports for disabled people get treated as something extra? The only difference between accommodations for nondisabled and disabled people is ableism. That's why the overworked Special Needs decided the time had come to move...

We All Need Accommodations: Excerpt From The White House Disability Pride Month Convening.The euphemism Special Needs, after many years of service, has filed for retirement. Nondisabled people receive countless supports, so why should supports for disabled people get treated as something extra? The only difference between accommodations for nondisabled and disabled people is ableism. That's why the overworked Special Needs decided the time had come to move... -

Libraries, Mental Health, & Accessibility with Mychal ThreetsHis brilliance, humor, and enchanting stories help people deepen their understanding of mental health. Mychal Threets @mychal3ts teaches how we can make libraries accessible for everyone, and sharing a stage with him at the White House was an absolute honor! Descriptive Transcript Mychal and Haben sit in chairs in an auditorium. Mychal types on a...

Libraries, Mental Health, & Accessibility with Mychal ThreetsHis brilliance, humor, and enchanting stories help people deepen their understanding of mental health. Mychal Threets @mychal3ts teaches how we can make libraries accessible for everyone, and sharing a stage with him at the White House was an absolute honor! Descriptive Transcript Mychal and Haben sit in chairs in an auditorium. Mychal types on a... -

Slow-shaming is Ableist — Excerpt 1 from the White House Disability Pride Month ConveningFull video on the White House YouTube channel Descriptive Transcript Haben: Haben Girma speaking. Hello, everyone. So I am going to start with a visual description. It's an accessibility practice for our blind audience, and anyone who's multitasking. (Laughter) Haben: I'm a Black woman in my 30s. I'm wearing a blue dress. In front of...

Slow-shaming is Ableist — Excerpt 1 from the White House Disability Pride Month ConveningFull video on the White House YouTube channel Descriptive Transcript Haben: Haben Girma speaking. Hello, everyone. So I am going to start with a visual description. It's an accessibility practice for our blind audience, and anyone who's multitasking. (Laughter) Haben: I'm a Black woman in my 30s. I'm wearing a blue dress. In front of... -

White House Disability Pride Month ConveningI'm excited to speak at the White House Disability Pride Month Convening on July 29th at 3:30 PM Eastern. We have a fantastic lineup of disability advocates speaking. You're all invited to tune in. In fact, July 29th is my birthday, so you're extra invited! The virtual event will have ASL interpretation and captioning. RSVP...

White House Disability Pride Month ConveningI'm excited to speak at the White House Disability Pride Month Convening on July 29th at 3:30 PM Eastern. We have a fantastic lineup of disability advocates speaking. You're all invited to tune in. In fact, July 29th is my birthday, so you're extra invited! The virtual event will have ASL interpretation and captioning. RSVP... -

![Video: Smelling & Tasting at the Disgusting Food Museum]() Smelling & Tasting at the Disgusting Food Museum in Malmö, SwedenMost museums have a visual culture, but this little museum takes guests on a multisensory tour. The Disgusting Food Museum also challenges our culinary biases. Descriptive Transcript Haben faces the camera holding a closed jar. Behind her is a wall of red and yellow cans. Haben: A lot of museums focus on visuals. I'm at...

Smelling & Tasting at the Disgusting Food Museum in Malmö, SwedenMost museums have a visual culture, but this little museum takes guests on a multisensory tour. The Disgusting Food Museum also challenges our culinary biases. Descriptive Transcript Haben faces the camera holding a closed jar. Behind her is a wall of red and yellow cans. Haben: A lot of museums focus on visuals. I'm at... -

Another Way for Blind People to Cross Streets: Tactile Traffic MapsTactile maps increase independence and freedom for blind people, and this technology puts traffic maps at our fingertips. Should cities around the world install these accessible pedestrian signals? Descriptive Transcript I'm standing beside a yellow and navy plastic control box near a crosswalk. Haben: A Swedish style of accessible pedestrian signals can now be found...

Another Way for Blind People to Cross Streets: Tactile Traffic MapsTactile maps increase independence and freedom for blind people, and this technology puts traffic maps at our fingertips. Should cities around the world install these accessible pedestrian signals? Descriptive Transcript I'm standing beside a yellow and navy plastic control box near a crosswalk. Haben: A Swedish style of accessible pedestrian signals can now be found... -

Deafblind Awareness Week: Everyone has a VoiceHelen Keller's birthday and Deafblind Awareness Week mark the perfect time to follow more Deafblind influencers. Here are some I follow, and if you know more tag them in the comments. Catarina Rivera @BlindishLatina Dr. Jasmine Simmons @ DrJasmineSimmons Loni Friedman @L.Friedmann Rebecca Alexander @RebeccaAlexander Molly Watt @MollyWattTalks Ashlea Brittney Hayes @AshleaBrittney Elsa Sjunneson @snarkbat...

Deafblind Awareness Week: Everyone has a VoiceHelen Keller's birthday and Deafblind Awareness Week mark the perfect time to follow more Deafblind influencers. Here are some I follow, and if you know more tag them in the comments. Catarina Rivera @BlindishLatina Dr. Jasmine Simmons @ DrJasmineSimmons Loni Friedman @L.Friedmann Rebecca Alexander @RebeccaAlexander Molly Watt @MollyWattTalks Ashlea Brittney Hayes @AshleaBrittney Elsa Sjunneson @snarkbat... -

A Swedish Hotel Welcoming Blind & Sighted Guests: AlmåsaHotels embracing accessibility win more customers. The Almåsa Sea Hotel owned by Sweden's Visually Impaired Foundation has multi-sensory experiences enjoyed by both blind and sighted guests. Descriptive Transcript A paved path, with a railing, guides visitors through a fragrant garden. Seeing Eye dog Mylo and Haben stride along the path toward a dock over gently...

A Swedish Hotel Welcoming Blind & Sighted Guests: AlmåsaHotels embracing accessibility win more customers. The Almåsa Sea Hotel owned by Sweden's Visually Impaired Foundation has multi-sensory experiences enjoyed by both blind and sighted guests. Descriptive Transcript A paved path, with a railing, guides visitors through a fragrant garden. Seeing Eye dog Mylo and Haben stride along the path toward a dock over gently... -

Haben Meets Paralympian & Adventurer Aron AndersonParalympian, speaker, author, and adventurer. Aron Anderson ( @AronAnderson1 ) is the first wheelchair user to reach the peak of Mount Kilimanjaro. And that is just the beginning! He leads groups on adventures around the world, showing people strategies to move through challenges. Descriptive Transcript Aron, Haben, and Seeing Eye dog Mylo are at a...

Haben Meets Paralympian & Adventurer Aron AndersonParalympian, speaker, author, and adventurer. Aron Anderson ( @AronAnderson1 ) is the first wheelchair user to reach the peak of Mount Kilimanjaro. And that is just the beginning! He leads groups on adventures around the world, showing people strategies to move through challenges. Descriptive Transcript Aron, Haben, and Seeing Eye dog Mylo are at a... -

Site-smelling in Alaska: The Good and the GrossMany people talk about sight seeing, but that's only one small part of travel. Let's embrace all the different ways we can experience our world! Descriptive Transcript A wide, paved path curves around a fountain with a majestic whale statue, and then continues alongside the channel with beautiful views of Douglas Island and downtown Juneau....

Site-smelling in Alaska: The Good and the GrossMany people talk about sight seeing, but that's only one small part of travel. Let's embrace all the different ways we can experience our world! Descriptive Transcript A wide, paved path curves around a fountain with a majestic whale statue, and then continues alongside the channel with beautiful views of Douglas Island and downtown Juneau.... -

A Tactile Tour of Alaska’s Theatre OrganAs a Deafblind person in a complicated relationship with music, stepping inside this theater organ deepened my appreciation and understanding of this extraordinary instrument. Alaska's only working theater organ, older than the state, continues playing lovely music thanks to the Alaska State Museum, talented organists, and the passionate locals and tourists who attend the free...

A Tactile Tour of Alaska’s Theatre OrganAs a Deafblind person in a complicated relationship with music, stepping inside this theater organ deepened my appreciation and understanding of this extraordinary instrument. Alaska's only working theater organ, older than the state, continues playing lovely music thanks to the Alaska State Museum, talented organists, and the passionate locals and tourists who attend the free... -

Add Descriptive Transcripts to Make Your Videos More AccessibleIt's Global Accessibility Awareness Day! Adding descriptive transcripts to videos helps Deafblind people and others who process information through text. Share this tip. Happy GAAD! Add Descriptive Transcripts to Make Your Videos More Accessible Descriptive Transcript Haben, a Black woman in her thirties with long dark hair, speaks to the camera, a vibrant blue wall...

Add Descriptive Transcripts to Make Your Videos More AccessibleIt's Global Accessibility Awareness Day! Adding descriptive transcripts to videos helps Deafblind people and others who process information through text. Share this tip. Happy GAAD! Add Descriptive Transcripts to Make Your Videos More Accessible Descriptive Transcript Haben, a Black woman in her thirties with long dark hair, speaks to the camera, a vibrant blue wall... -

Alaskan Whale-watching Adventures while DeafblindWhale watching tours may seem purely visual, but thoughtful guides create interactive experiences that are fun even though I can't see the whales! Descriptive Transcript Experienced guide Laurie Clough approaches Haben holding a three-feet long, orange sea star. Haben gently studies the star with her fingers. Hundreds of tiny tube feet, yellow on the ends,...

Alaskan Whale-watching Adventures while DeafblindWhale watching tours may seem purely visual, but thoughtful guides create interactive experiences that are fun even though I can't see the whales! Descriptive Transcript Experienced guide Laurie Clough approaches Haben holding a three-feet long, orange sea star. Haben gently studies the star with her fingers. Hundreds of tiny tube feet, yellow on the ends,... -

London vs Paris: Accessible Pedestrian SignalsLondon or Paris? Accessible pedestrian signals feel different across the channel, with their own pros and cons. Which style do you prefer and why? Descriptive Transcript Haben is standing at a crosswalk in London. She is wearing a lavender coat and long, gold earrings. She is speaking directly to the camera. Cars and red, double...

London vs Paris: Accessible Pedestrian SignalsLondon or Paris? Accessible pedestrian signals feel different across the channel, with their own pros and cons. Which style do you prefer and why? Descriptive Transcript Haben is standing at a crosswalk in London. She is wearing a lavender coat and long, gold earrings. She is speaking directly to the camera. Cars and red, double... -

International Guide Dog DayHappy International Guide Dog Day! Gifts made to The Seeing Eye in honor of the day will be doubled! Seeing Eye Donation Page Haben and her Seeing Eye dog Mylo walk through a crowded airport. Haben is wearing a long lilac overcoat and a floral dress; she's wheeling a suitcase beside her. A man carrying...

International Guide Dog DayHappy International Guide Dog Day! Gifts made to The Seeing Eye in honor of the day will be doubled! Seeing Eye Donation Page Haben and her Seeing Eye dog Mylo walk through a crowded airport. Haben is wearing a long lilac overcoat and a floral dress; she's wheeling a suitcase beside her. A man carrying... -

Disability Allyship: Milana Vayntrub & Haben GirmaDisability allyship has two crucial pillars: 1. Ask disabled people what we need, and 2. Based on those answers, take action to remove barriers. Actor, director, and comedian Milana Vayntrub role models disability allyship. AT&T invited Milana and I to share a stage, sparking a beautiful connection. We filmed this conversation after our electric keynote....

Disability Allyship: Milana Vayntrub & Haben GirmaDisability allyship has two crucial pillars: 1. Ask disabled people what we need, and 2. Based on those answers, take action to remove barriers. Actor, director, and comedian Milana Vayntrub role models disability allyship. AT&T invited Milana and I to share a stage, sparking a beautiful connection. We filmed this conversation after our electric keynote.... -

How the Hand of Ableism Hijacks a Touch Tour for Blind Patrons at the British MuseumThe British Museum invites blind patrons to touch ancient sculptures, but when I placed my hands on one of these treasures an angry sighted person started harassing me. Video of the incident sparked outrage online. In March 2023 the BBC asked me to share what happened, and they aired a recording of me reading a...

How the Hand of Ableism Hijacks a Touch Tour for Blind Patrons at the British MuseumThe British Museum invites blind patrons to touch ancient sculptures, but when I placed my hands on one of these treasures an angry sighted person started harassing me. Video of the incident sparked outrage online. In March 2023 the BBC asked me to share what happened, and they aired a recording of me reading a... -

Nikil’s Treasures: The Braille & Large Print Books at India’s Accessible Reading Materials LibraryUgly and too expensive, scoffed critics. But the astounding beauty and creativity in these books speaks volumes! Dr. Namita Jacob felt frustrated by the scarcity of accessible books in India. She founded the Accessible Reading Materials Library, Chetana Charitable Trust, a community of volunteers making Braille, large print, joy-filled books that allow blind kids and...

Nikil’s Treasures: The Braille & Large Print Books at India’s Accessible Reading Materials LibraryUgly and too expensive, scoffed critics. But the astounding beauty and creativity in these books speaks volumes! Dr. Namita Jacob felt frustrated by the scarcity of accessible books in India. She founded the Accessible Reading Materials Library, Chetana Charitable Trust, a community of volunteers making Braille, large print, joy-filled books that allow blind kids and... -

![Video: Haben feeling a black robotic hand that is signing the letter "S"]() A New Tool for Deafblind People: A Signing Robot HandIf you can't read Braille, what do you think of reading a robot hand? A New Tool for Deafblind People: A Signing Robot Hand Video Description A black-gloved, human-sized hand sticks up from a base with about a dozen buttons. As it signs the American Sign Language letters S-U-N it makes a mechanical whirring sound....

A New Tool for Deafblind People: A Signing Robot HandIf you can't read Braille, what do you think of reading a robot hand? A New Tool for Deafblind People: A Signing Robot Hand Video Description A black-gloved, human-sized hand sticks up from a base with about a dozen buttons. As it signs the American Sign Language letters S-U-N it makes a mechanical whirring sound.... -

Seeing Eye Dog Mylo and Haben Visiting Juneau, AlaskaOn Wednesday May 1, 2024 the Juneau Public Library is hosting a reading and discussion with Haben Girma. She will read, in Braille, from her book Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law. She welcomes questions, and Mylo does, too! Join us for an engaging conversation on how we all can make our communities...

Seeing Eye Dog Mylo and Haben Visiting Juneau, AlaskaOn Wednesday May 1, 2024 the Juneau Public Library is hosting a reading and discussion with Haben Girma. She will read, in Braille, from her book Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law. She welcomes questions, and Mylo does, too! Join us for an engaging conversation on how we all can make our communities... -

An iPhone Feature Helping Deaf/Hard of Hearing People: Live CaptionsMy friend Lainey Feingold showed her 91-year-old dad how to turn on Live Captions on his iPhone, and now he loves how much easier phone calls are for him. How many other elders don't know about Live Captions? Everyone, including our elders, should have communication tools that help facilitate connection. Share accessibility features with elders...

An iPhone Feature Helping Deaf/Hard of Hearing People: Live CaptionsMy friend Lainey Feingold showed her 91-year-old dad how to turn on Live Captions on his iPhone, and now he loves how much easier phone calls are for him. How many other elders don't know about Live Captions? Everyone, including our elders, should have communication tools that help facilitate connection. Share accessibility features with elders... -

![Video: Haben feeds paper into her Juliet Pro Embosser]() Sweet Juliet, Free of Planned ObsolesceA Blind Woman Brailling Like It's 1995 This Juliet embosser helped me through college and law school. She followed me from Portland to Boston to Oakland, and dents along her surface commemorate each trip. Newer, lighter, flashier Braille printers exist, but this still works for me. Descriptive Transcript I'm feeding paper into a large machine,...

Sweet Juliet, Free of Planned ObsolesceA Blind Woman Brailling Like It's 1995 This Juliet embosser helped me through college and law school. She followed me from Portland to Boston to Oakland, and dents along her surface commemorate each trip. Newer, lighter, flashier Braille printers exist, but this still works for me. Descriptive Transcript I'm feeding paper into a large machine,... -

![Video: A Bias Challenge at the Exploratorium]() A Bias Challenge at the ExploratoriumA Bias Challenge at the Exploratorium Can you get past assumptions of what a drinking fountain should look like? The Exploratorium , a science museum in San Francisco, has a sign saying both fountains are safe. Which one would you sip from? Most people pick the traditional fountain. The exhibit invites people to notice that...

A Bias Challenge at the ExploratoriumA Bias Challenge at the Exploratorium Can you get past assumptions of what a drinking fountain should look like? The Exploratorium , a science museum in San Francisco, has a sign saying both fountains are safe. Which one would you sip from? Most people pick the traditional fountain. The exhibit invites people to notice that... -

Learning Italian Sign Language at a Deaf-owned wine bar in ItalyDo you learn new sign languages when you travel? One of my favorite memories from Italy: getting to know Barbara Voyageuse Verna, a Deafblind woman who is working to establish a Deafblind association. We met up at the Deaf-owned Ânma winebar in Reggio Emilia. The warm space, with its scrumptious snacks and drinks, welcomes people...

Learning Italian Sign Language at a Deaf-owned wine bar in ItalyDo you learn new sign languages when you travel? One of my favorite memories from Italy: getting to know Barbara Voyageuse Verna, a Deafblind woman who is working to establish a Deafblind association. We met up at the Deaf-owned Ânma winebar in Reggio Emilia. The warm space, with its scrumptious snacks and drinks, welcomes people... -

Visiting Albany Law SchoolVisiting Albany Law School introduced me to many enthusiastic advocates, some who are new to accessibility and some who have been championing disability justice for years! Thank you, Albany, for inviting me to deliver the 2024 author lecture!

Visiting Albany Law SchoolVisiting Albany Law School introduced me to many enthusiastic advocates, some who are new to accessibility and some who have been championing disability justice for years! Thank you, Albany, for inviting me to deliver the 2024 author lecture! -

Reading, in Braille, from Haben: the Deafblind Woman who Conquered Harvard LawTranscript The reading is an excerpt from Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law by Haben Girma with a Forward by Stephen Curry. Video Description : Pam Johnson stands beside me, signing in American Sign Language as I speak. I'm sitting at a table reading from a short stack of Braille pages, and my...

Reading, in Braille, from Haben: the Deafblind Woman who Conquered Harvard LawTranscript The reading is an excerpt from Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law by Haben Girma with a Forward by Stephen Curry. Video Description : Pam Johnson stands beside me, signing in American Sign Language as I speak. I'm sitting at a table reading from a short stack of Braille pages, and my... -

Angels of ImpactHow do we create a future where poverty exists only in museum exhibits? Before she became CEO of Angels of Impact , Laina Raveendran Greene studied this question in and outside the classroom. She volunteered and donated to charities, but surely there was more we could do? Laina authored the guidebook Sustainable Impact: How Women...

Angels of ImpactHow do we create a future where poverty exists only in museum exhibits? Before she became CEO of Angels of Impact , Laina Raveendran Greene studied this question in and outside the classroom. She volunteered and donated to charities, but surely there was more we could do? Laina authored the guidebook Sustainable Impact: How Women... -

World Braille Day 2024It's World Braille Day! A blind teacher named Louis Braille created this tactile reading system, and now his birthday, January 4, is a day to celebrate this marvelous way to read! Braille exists in multiple languages, and I recently had the honor of meeting Sabriye Tenberken, also blind, who invented and taught Tibetan Braille. In...

World Braille Day 2024It's World Braille Day! A blind teacher named Louis Braille created this tactile reading system, and now his birthday, January 4, is a day to celebrate this marvelous way to read! Braille exists in multiple languages, and I recently had the honor of meeting Sabriye Tenberken, also blind, who invented and taught Tibetan Braille. In... -

Visiting Kanthari, a social impact institute in IndiaInspiration should lead to action. A blind woman who invented Tibetan Braille and overcame political red tape and ableism, Sabriye Tenberken both role models and teaches social impact. Want to start an NGO? Need help finding donors? Want advise navigating oppressive bureaucracy? Take the course at Kanthari, this social impact institute I was very lucky...

Visiting Kanthari, a social impact institute in IndiaInspiration should lead to action. A blind woman who invented Tibetan Braille and overcame political red tape and ableism, Sabriye Tenberken both role models and teaches social impact. Want to start an NGO? Need help finding donors? Want advise navigating oppressive bureaucracy? Take the course at Kanthari, this social impact institute I was very lucky... -

Haben Appointed Commissioner of the WHO Commission on Social ConnectionI have exciting news to share: the World Health Organization (WHO) has appointed me Commissioner of the new Commission on Social Connection! The WHO established this new Commission because loneliness and social isolation impact public health around the globe. As someone who struggled with isolation, as a Deafblind woman in a sighted, hearing world, as...

Haben Appointed Commissioner of the WHO Commission on Social ConnectionI have exciting news to share: the World Health Organization (WHO) has appointed me Commissioner of the new Commission on Social Connection! The WHO established this new Commission because loneliness and social isolation impact public health around the globe. As someone who struggled with isolation, as a Deafblind woman in a sighted, hearing world, as... -

Disability SimulationsShould event planners ask attendees to close their eyes, walk around the hotel for an hour, and imagine what it's like being blind? No, and this article explains why disability simulation exercises are problematic. Article: Accessibility Advocates Oppose Disability Simulations

-

National Deafblind Equipment Distribution Program Troubles in CaliforniaMany deafblind people rely on the FCC's National Deafblind Equipment Distribution Program for braille tech & training, which can cost thousands of dollars. But Californians are struggling to access the program. Dear FCC, please find a new partner organization in CA. Read the report: When there is no accountability, accessibility suffers.

National Deafblind Equipment Distribution Program Troubles in CaliforniaMany deafblind people rely on the FCC's National Deafblind Equipment Distribution Program for braille tech & training, which can cost thousands of dollars. But Californians are struggling to access the program. Dear FCC, please find a new partner organization in CA. Read the report: When there is no accountability, accessibility suffers. -

World Health Organization Technical Advisory Group on Social ConnectionThe World Health Organization is creating a Technical Advisory Group on Social Connection to study what causes social isolation and how to create healtheir, more connected communities. If you know someone with ideas for the WHO, please encourage them to apply. Article: Call for Experts -- Technical Advisory Group on Social Connection

-

![Video: Learning Mexican Sign Language]() Learning Mexican Sign LanguageAmerican Sign Language (ASL) is different from Mexican Sign Language (LSM). A patient & gifted Deaf LSM instructor, Yahir Alejandro taught me these signs. Will you, too, learn LSM or your local sign language? For more from Yahir, follow him on Instagram @YahirAlejandroRM . Video description: Yahir is a young, sighted, Deaf man, and Haben...

Learning Mexican Sign LanguageAmerican Sign Language (ASL) is different from Mexican Sign Language (LSM). A patient & gifted Deaf LSM instructor, Yahir Alejandro taught me these signs. Will you, too, learn LSM or your local sign language? For more from Yahir, follow him on Instagram @YahirAlejandroRM . Video description: Yahir is a young, sighted, Deaf man, and Haben... -

Binational Forum of Deaf CultureServing as the keynote speaker for the first Binational Forum of Deaf Culture, I met many passionate advocates working to increase accessibility in Mexico. Some things I learned: The state of Sonora officially recognized Mexican Sign Language (LSM) as a language in 2022, thanks to the Deaf community's awareness campaign. There is an extreme shortage...

Binational Forum of Deaf CultureServing as the keynote speaker for the first Binational Forum of Deaf Culture, I met many passionate advocates working to increase accessibility in Mexico. Some things I learned: The state of Sonora officially recognized Mexican Sign Language (LSM) as a language in 2022, thanks to the Deaf community's awareness campaign. There is an extreme shortage... -

IndeedSociety tells disabled job seekers, "Just work harder." But many already exceed the efforts of non disabled people. It's employers who must work harder to fight ableism. Grateful to be able to share this message with HR professionals during my keynote at Indeed FutureWorks!

IndeedSociety tells disabled job seekers, "Just work harder." But many already exceed the efforts of non disabled people. It's employers who must work harder to fight ableism. Grateful to be able to share this message with HR professionals during my keynote at Indeed FutureWorks! -

Haben at GartnerAfter my keynote at Gartner's conference an attendee told me they're inspired to make their websites and apps more accessible to disabled people. My favorite kind of inspiration!

Haben at GartnerAfter my keynote at Gartner's conference an attendee told me they're inspired to make their websites and apps more accessible to disabled people. My favorite kind of inspiration! -

San Francisco Lighthouse UnionBlind workers at the San Francisco Lighthouse are organizing a union, the first blind-centered union in California! So exciting! Hoping the LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired's management decides to recognize the new union Article: Blind, visually impaired workers at LightHouse kick off union --- first of its kind in Bay Area

-

Ponta da Ilha LighthouseThe lighthouse had their first blind visitor, and they turned it into an opportunity to search high and low for all the tactile experiences! They showed me the reserve light, the antique light, and they invited my guide dog and I to climb the stairs as high as we were comfortable going. The long, spiraling...

Ponta da Ilha LighthouseThe lighthouse had their first blind visitor, and they turned it into an opportunity to search high and low for all the tactile experiences! They showed me the reserve light, the antique light, and they invited my guide dog and I to climb the stairs as high as we were comfortable going. The long, spiraling... -

Ocean BreezeShe loves her island, but doctors said if she wants to learn braille she has to leave her home for mainland Portugal. This is ableism. Institutions around the world have traditionally removed disabled people from their homes and placed them in special schools and centers. While many of these centers provide great learning opportunities, we...

Ocean BreezeShe loves her island, but doctors said if she wants to learn braille she has to leave her home for mainland Portugal. This is ableism. Institutions around the world have traditionally removed disabled people from their homes and placed them in special schools and centers. While many of these centers provide great learning opportunities, we... -

He Fits! Mylo on Azores AirlinesHe fits! Azores Airlines claims the only way a service dog can fit is by having a disabled person sit alone next to an empty seat. Instead of making assumptions based on a dog's weight, airlines should ask us how we'd like to fly with our dogs. Many disabled people have strategies for traveling with...

He Fits! Mylo on Azores AirlinesHe fits! Azores Airlines claims the only way a service dog can fit is by having a disabled person sit alone next to an empty seat. Instead of making assumptions based on a dog's weight, airlines should ask us how we'd like to fly with our dogs. Many disabled people have strategies for traveling with... -

Augusto Arruda Pineapple PlantationConfession: I thought pineapples grew on trees. Reason 98973 to increase accessibility at public gardens. Thanks to the Augusto Arruda Pineapple Plantation for welcoming my guide dog!

Augusto Arruda Pineapple PlantationConfession: I thought pineapples grew on trees. Reason 98973 to increase accessibility at public gardens. Thanks to the Augusto Arruda Pineapple Plantation for welcoming my guide dog! -

Mylo at the Azorean BeachSeeing Eye dog Mylo is with me in the Azores! Thank you to everyone who shared my video describing Azores Airlines' policy of separating disabled travelers from family/friends! The U.S. Department of Transportation confirmed they are investigating Azores Airlines. We flew here with United Airlines, which generously upgraded us to bulkhead seats that gave Mylo...

Mylo at the Azorean BeachSeeing Eye dog Mylo is with me in the Azores! Thank you to everyone who shared my video describing Azores Airlines' policy of separating disabled travelers from family/friends! The U.S. Department of Transportation confirmed they are investigating Azores Airlines. We flew here with United Airlines, which generously upgraded us to bulkhead seats that gave Mylo... -

![Video: This airline separates disabled travelers from family/friends]() This airline separates disabled travelers from family/friendsTranscript (Haben speaking): Because I'm blind, an airline is saying I have to sit alone. We booked side-by-side seats. But when they found out I'm blind, they separated us. They're claiming it's their policy that if a person has a service dog over 55 pounds, they need a separate extra seat because they assume the...

This airline separates disabled travelers from family/friendsTranscript (Haben speaking): Because I'm blind, an airline is saying I have to sit alone. We booked side-by-side seats. But when they found out I'm blind, they separated us. They're claiming it's their policy that if a person has a service dog over 55 pounds, they need a separate extra seat because they assume the... -

“Disability Sparks Innovation” | Haben Profiled on Forbes'Disability Sparks Innovation': Insights From Deafblind Human Rights Lawyer Haben Girma

“Disability Sparks Innovation” | Haben Profiled on Forbes'Disability Sparks Innovation': Insights From Deafblind Human Rights Lawyer Haben Girma -

It’s My Birthday!It's my birthday! Reading is one of my favorite things, especially humor-filled stories, so pleas send me your book recommendations! Highlights from this past year: Year of the Tiger by Alice Wong True Biz by Sara Novic Joan is Okay by Weike Wang The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman Sipping Dom Perignon through a...

It’s My Birthday!It's my birthday! Reading is one of my favorite things, especially humor-filled stories, so pleas send me your book recommendations! Highlights from this past year: Year of the Tiger by Alice Wong True Biz by Sara Novic Joan is Okay by Weike Wang The Thursday Murder Club by Richard Osman Sipping Dom Perignon through a... -

Disability Pride MonthJuly is Disability Pride Month, an invitation to reflect on accessibility in our communities. What are you inspired to do, what action will you take, to make your organization more inclusive? Article: 'Disability Sparks Innovation': Insights From Deafblind Human Rights Lawyer Haben Girma

-

On Parks, Guide Dogs, & AbleismPark rangers stop us every time. "No dogs allowed. You need to leave." Their surprise upon learning it's a real, actual Seeing Eye dog puzzles me. The Parks & Recreation Department trains them to identify coyotes and mountain lions, but not Seeing Eye dogs? But today was different. The ground shook as their truck drove...

On Parks, Guide Dogs, & AbleismPark rangers stop us every time. "No dogs allowed. You need to leave." Their surprise upon learning it's a real, actual Seeing Eye dog puzzles me. The Parks & Recreation Department trains them to identify coyotes and mountain lions, but not Seeing Eye dogs? But today was different. The ground shook as their truck drove... -

Speaking at DeloitteI delivered a keynote at Deloitte University , and imagine my delight in discovering this tactile, Deafblind-accessible sign! The design allows people to see or feel equity.