The British Museum invites blind patrons to touch ancient sculptures, but when I placed my hands on one of these treasures an angry sighted person started harassing me. Video of the incident sparked outrage online. In March 2023 the BBC asked me to share what happened, and they aired a recording of me reading a version of this essay. You can watch the video, listen to me reading the essay, or read the text.

Essay and Descriptive Video Transcript

My name is Haben Girma. Allow me to share a recent experience.

The officer stands between me and the British Museum. First he says no dogs. Then he takes another look and asks, “If that’s a guide dog, why isn’t it wearing the proper vest?”

All week sighted people have been asking, “Why isn’t he wearing green?” Or, “How come he’s not wearing the sign?” Many service dogs have neon green vests, and many guide dogs wear white harnesses with large neon signs. But UK and US laws don’t require assistance dogs to wear specific colors or textiles. In America we have over a dozen different guide dog schools, and each one has a unique harness.

My Mylo graduated from The Seeing Eye, the world’s oldest guide dog school. Its instructors have helped start many of the guide dog schools around the world, including the UK.

(The video zooms in on Mylo’s leather harness.)

The Seeing Eye harness has the school name embossed in an elegant font. The soft brown leather sparkles with pops of silver, complimenting Mylo’s black and tan, genuine fur coat.

The officer listens as I share what I’ve been teaching Londoners: it’s the training that makes a guide dog, not the outfit.

The officer not only lets us in, but invites us to skip the queue! Queue hopping sparks heated debate in the blind community. We want equality, not special treatment. I am an avid walker, dancer, and the author of Haben: The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law. Deafblindness doesn’t prevent me from standing in lines,and normally I do. Unless someone insults my dog.

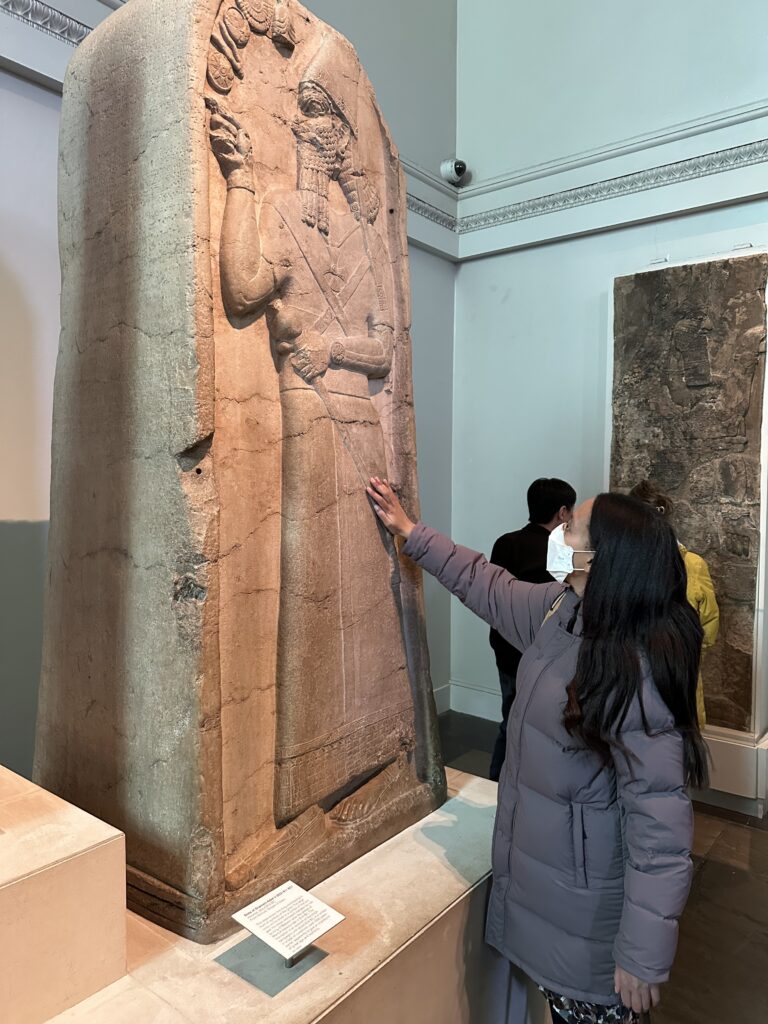

Inside the museum, I approach an exhibit. Mylo stands patiently beside me as my fingers glide over an Egyptian foot. Signs throughout the room prohibit touching. That ban is for the sighted. Only blind people can touch ancient treasures, and signs indicate this with a symbol that looks like a stylized eye.

Equality can mean different ways of engaging. If you have working eyeballs, use them. If not, tap into your other senses.

I continue through the museum, delighting in all the history at my fingertips. This large sculpture, The Sacred boat of Queen Mutemwia, is from 1400 BCE! In the world outside museums, aged objects typically languish under layers of dust. The pristine surface of this piece feels disorienting. What does feeling old truly mean? Dents and scrapes carry the memories of past adventures, each crack encasing a tale yearning to unfold. Striving to read the stories, I gently slide my fingers over this tribute to an Egyptian queen. Suddenly — Jab! Jab! My arm gets stabbed by an angry finger.

(The video shows Haben feeling the top of The Sacred Boat of Queen Mutemwia when someone intentionally slams their finger into her shoulder. The hand of ableism appears white, and wears a smart watch.)

Mylo looks up in alarm. The person furiously gestures at the don’t-touch sign. I don’t see them, of course, and turn back to the sculpture. A museum employee stops the raging sightie, explaining that blind people are allowed to touch exhibits.

Sadly, sighted people harassing blind people, grabbing and pushing us, is not uncommon. If I may offer a suggestion: the museum should block entry to sighted people. They’re quite poorly behaved.

Not only that, turning off the lights, an accommodation for sighted people, would reduce the electricity bill. Think about it!

In all seriousness, sighted people need to stop making assumptions. Many disabilities are not visible, and some visible symbols, such as guide dog harnesses, appear different around the world.

We shouldn’t have to dress a certain way or carry a specific symbol. Nondisabled people must work harder to eradicate disability bias. Museum visitors playing culture police may end up hurting someone. If you have concerns about another patron, bring it up with the staff.

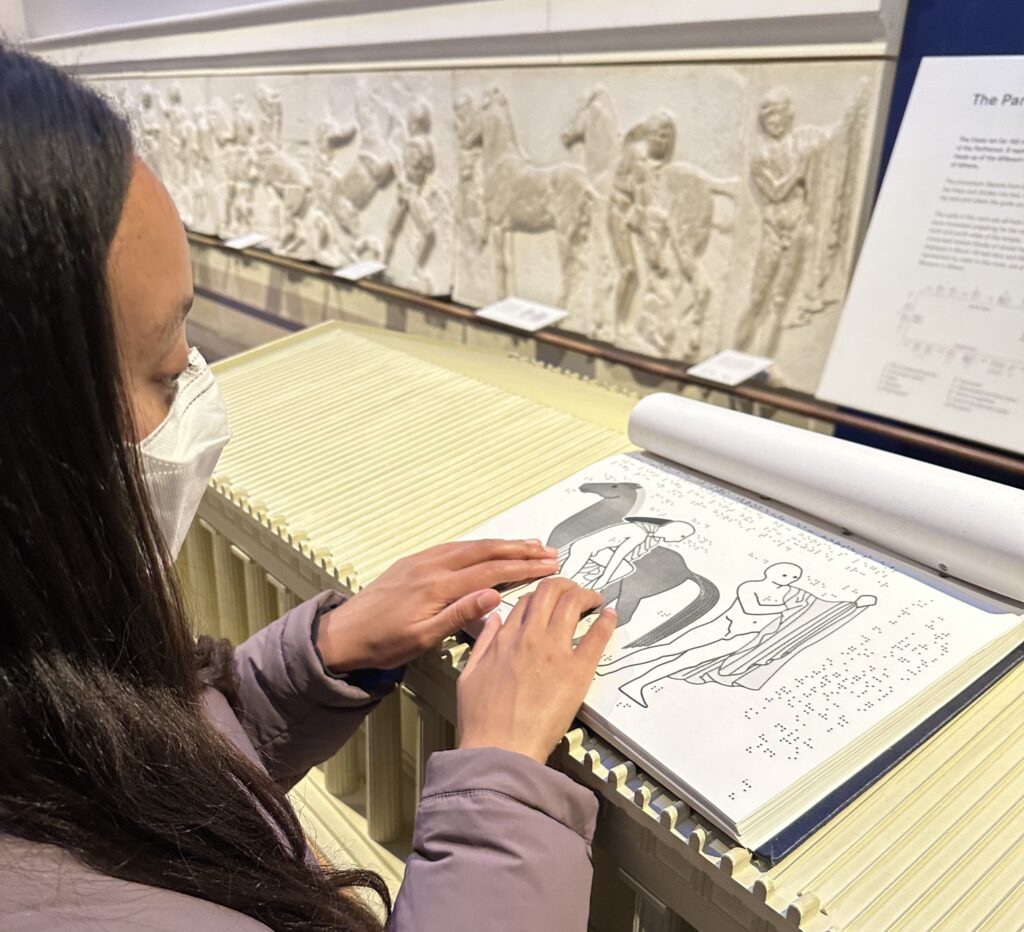

Touring the British Museum is still one of the highlights from my trip to London. They have informational books in braille, large print, as well as audio guides. Inviting us to touch ancient art remains a rare gift. Only a few museums around the world do this, but it’s my hope more will follow.